The load, an elegant sculpture hours in the making, nanoseconds to destroy.

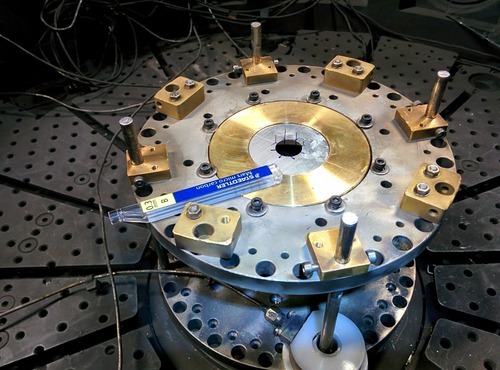

We’ve been working on it for days, probably. The load is small, no larger than a fist, an elegant sculpture of metal or carbon, nestled in the centre of a steel cylinder, surrounded by thick glass windows. It might have wires thinner than a human hair, or a complex arrangement of foils, loops, cables and plates. We’ve surrounded it with glass and sheets of metal to deflect and absorb the destruction that will ensue. There are lasers pointed at it, through it, into it, from the side, and above, with lenses and apertures like the remnants of a camera strewn across the gleaming metal tables.

Turbo pumps bring the pressure in the chamber down by a factor of 10 million.

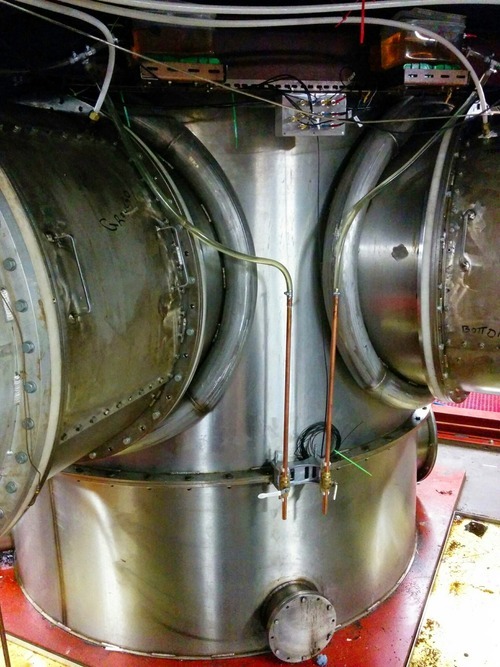

The steel chamber is pumped out by turbo molecular pumps, mini jet engines that bat air molecules down and out, stretching and thinning the air until you can’t call what’s left a gas, really, just a handful of particles bouncing off walls. The pumps work overnight, and by morning we’re ready. Everything has been checked and rechecked, numbers shouted across the lab, written down, checked again, argued over, references consulted, phone calls made, but here it is, we’ve done everything we can think of and if it goes wrong now, well, we’ll just have to do it again, and better.

Trigger units set to single shot mode – once they get a trigger signal, they will delay it and repeat it tens or hundreds of nanoseconds later to get the timing just right.

Press all the buttons, flashing red to a solid glow, ready to go, only one shot now, the tests are over, close the door and seal up the electronics, delicate and sensitive, shielded inside a box of steel from the electromagnetic maelstrom that will strike soon. Downstairs we go, lights off above, shouts upstairs to check no one’s there, unaware, sirens on, warning lights flashing, doors closed and ear protection donned. With a clunk, the power supplies start, two unassuming beige boxes with little dials and brightly coloured buttons, and digital displays the count upwards in synchrony as we watch.

A Marx bank, four metres tall and filled with fifty thousand litres of oil and a lot of electronics

Inside the four towering red tanks, charge trickles into the four Marx banks, regulated, counted, take one electron from this side, put it on that side, stored in capacitors, polished metal boxes stacked in four columns of six, with resistors full of pale blue liquid forming the arteries through which the charges move, the lot mired in deep brown oil that stirs slightly as the voltage rises. Minutes pass, and we count them in volts, calling out the potentials positive and negative, eyes scanning all the dials, the displays, the quivering needles. I am restless and nervous and the pressure in my head is rising in anticipation and I just want it to work so badly, but I’ve got to hold it back and keep a close watch, be a dispassionate scientist unconcerned by the days (weeks?) of preparation this moment embodies. Finally it’s ready, good to go, all set, and our nerves can’t take it any more either, so we thump red buttons that protect the power supplies from the inevitable electromagnetic backlash, and hit a small green blinking light nestled in amongst a tangle of wires. It’s labelled ‘MAGPIE GO BOOM’, and boy does it.

The MAGPIE trigger button

The Trigger Marx, a smaller Marx bank that triggers the larger Marx banks. What triggers the Trigger Marx? That is one of the deep mysteries.

To us, it’s over in an instant. To the machine, it takes a little longer. A pulse of voltage races upstairs, slamming a valve shut to protect the precious pumps perched behind, isolating the steel cylindrical chamber in which the everything plays out from the rest of the lab. Another signal streaks back downstairs, giving the all-clear, the time is near, counters starting, ticking, delaying, waiting for their moment, and at the back of the lab, in a brown box the size of a coffin the trigger bank sputters into life, first one spark, then two, three, four, the voltage building and racing down thick black cables towards the four looming red tanks.

A gas switch, not in a bank. We fill them with sulphur hexafluoride, a gas which is very resistant to electrical breakdown.

Inside the tanks, all is peaceful. The capacitors sit quietly, taking the strain of the huge voltage placed upon them, holding the positive charges away from the negative. The gas switches are silent, cylinders with brass domes, and the electric field is huge, and it rips electrons out of the metal and hurls them towards the opposite side, each trying to make their mark with a spark. But the gas is too thick, the electrons get nowhere, they collide with a fat molecule and lose their energy, and the roiling, boiling sea of evaporating electrons never makes it to the opposite shore.

But now the trigger signal has arrived, its long journey around the lab complete, and it smashes the tranquillity, gives the switches a smack with an electric hammer, shakes them up a bit, and it’s overwhelming, the electrons surge across the deepest switch, and as they go they light it up, the gas glows, current flows, negative connects to positive, and before you know it it’s got to the next switch up, the current rising, and that ones goes too, unstoppable now, building in power, a surge of electricity that breaks down all the gas in its path, and before you know it, twelve switches glowing, the voltage is a dozen times larger, and it can’t be contained any more, it’s got to get out, and it finds a way through a thick copper pipe that passes through the wall of the tank, encircled by plastic.

One of the pulse forming lines, metal pipes a metre in diameter, like coaxial cables but filled with deionised water.

It’s electromagnetic now, you see, not static charges and stale potentials but fields that skitter and skate across shiny surfaces, propagating past plastics, polarising, near the speed of light, fields that wobble themselves and each other, interfering, bouncing, reflecting, racing through a steel pipe a meter wide, filled with water that twists and turns, the molecules trying to align with the field that tears through them, but the water’s slow, too slow, and the wave will be past, long past by the time they’ve twisted into the right position, leaving the water dazed and confused, twisting aimlessly as dying wave echoes back and forth. But ahead there’s a wall, full stop, the wave slams on the brakes but can’t reflect, there’s too much voltage piling up behind it and it’s stuck.

The line gap trigger in all its glory. Screwdriver, buckets of oil and spare capacitors sold separately.

But not for long, for at the back of the lab, gurgling in its own vat of oil is another capacitor that’s been biding its time, waiting for its signal, and it’s got the go, gotta go, so it does, with a fizz and a pop, dumps the lot into four lines, identical lengths, voltage pulsing down, racing each other to the switches that are holding the four tidal surges of current separate. The switches are big, half a metre across, filled with gas (and plenty of it) that refuses to budge until it’s given a nudge, and then it goes, breaks down, glows, and there it is, the switch is closed, and the current rushes on.

The Vertical Transmission Line, where the four Marx banks discharge their electrical current so it can be deflected upwards to the experiment.

The four waves become one in a squat vertical pipe, steel still, three metres across, coaxial – it’s practical – and as the waves mingle and wash over each other they surge onwards, drawn upwards through the water. The walls close in, the gap narrows between the inner cylinder and the outer in the mighty MITL, magnetically insulating, voltage transmitting. The fields intensify as they’re crushed, and the forces are incredible, electrons ripped from the metal, trying to streak across the gap and spark, stop the show, but the current is intense and the magnetic field more so, and those errant electrons are whipped around and sent back the way they came. None cross, the MITL holds them off as it narrows, now half a metre, now a few centimetres across and here, at the breaking point, the current pulse enters the steel chamber in a silent, motionless vacuum and the experiment really begins.

To be continued.